TOPOGRAPHIES OF THE SOUL

By Cynthia Penna 2022

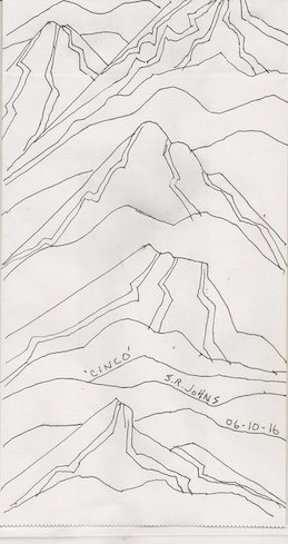

TOPOGRAPHY, as described by the Oxford Dictionary, “The graphic representation, viewed from a plane or high altitude, of a certain area of land, of reduced extension (no more than 30 km) so that the sphericity of the Earth can be neglected."

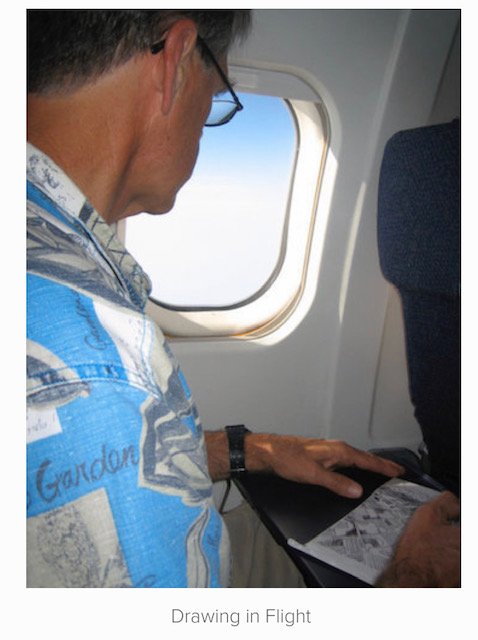

Stephen Robert Johns is not interested in topographic maps commonly found on the market; he documents and invents his own topographies through a reversal of topographical science, aimed to create a somewhat unreal and abstract one, no longer scientifically based, but on an artistic basis, but not without realistic details that reveal where he has passed. He does draw that what he sees…but with an artistic license…

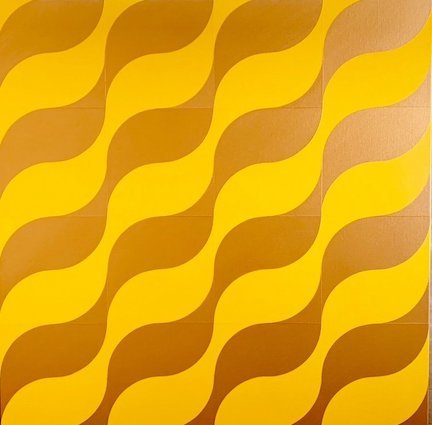

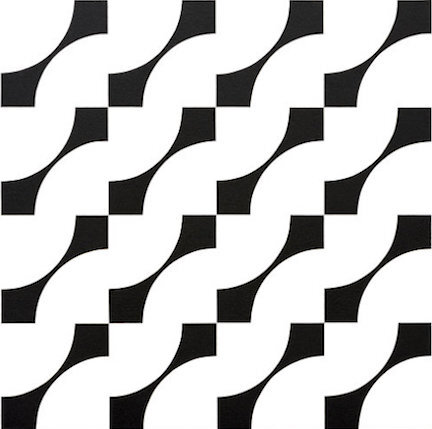

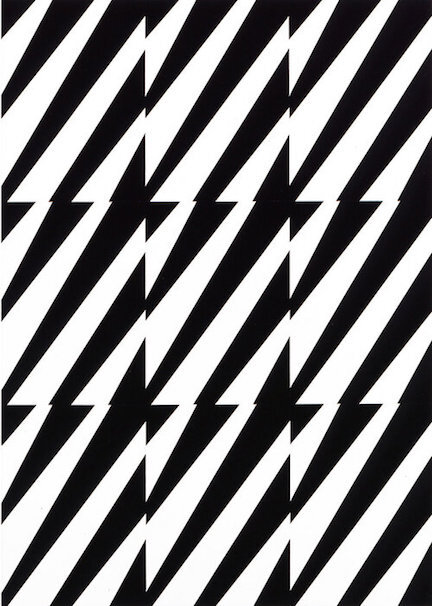

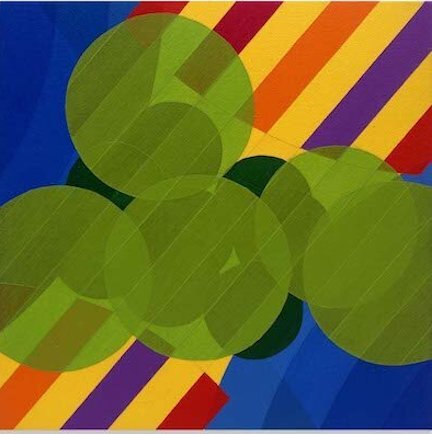

From the height of the 10,000 meters during his flights between Los Angeles CA and San Jose Costa Rica, both cities where he lives and works, Johns draws new topographies; observes the underlying ground which has a much broader horizon than the one we are used to seeing with our limited "flat-land” view. He grasps a more curvilinear horizon and perspective and overturns the terms of the "non-spherical" view of the earth's surface (which scientifically serves to create the real topographies), focusing precisely on those curves, those waves of the ground, those sinuous lines of rivers and land that he transforms into pictorial works as drawings, and later paintings, of an artistic style named Organic Geometry.

Johns defines his work as pertaining to "spatial organic geometry", that is to say an organic interpreted representation of space where the mathematical / geometric rules undergo intense modifications of their scientific basis to delve into the world of the imaginary art and that of what the artist sees and draws.

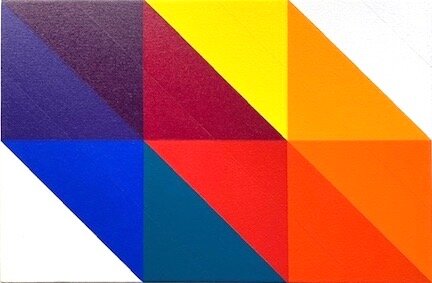

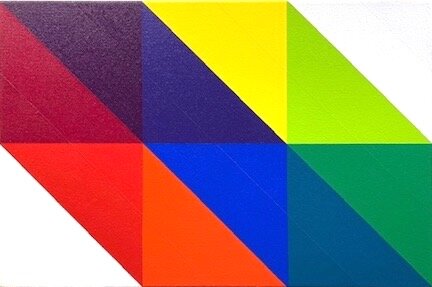

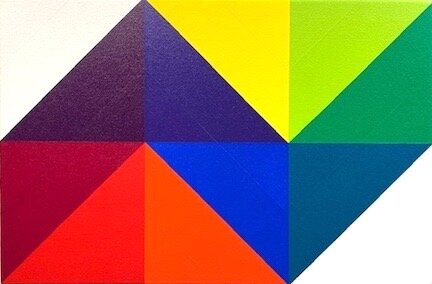

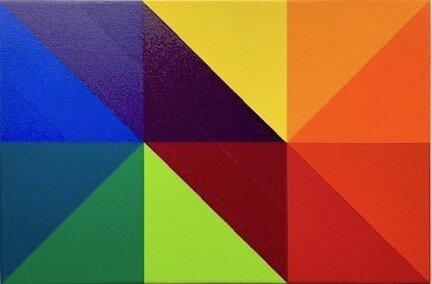

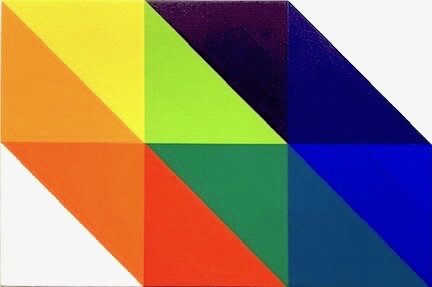

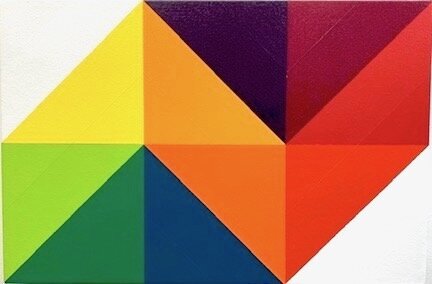

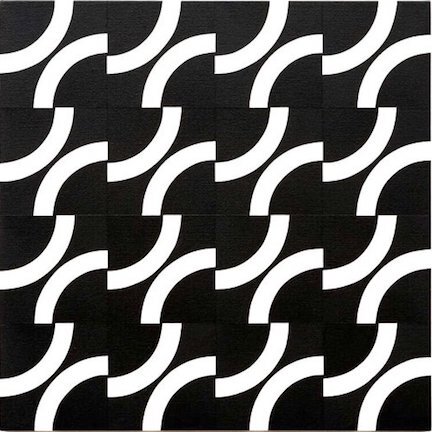

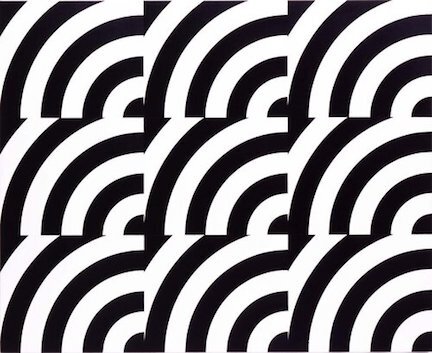

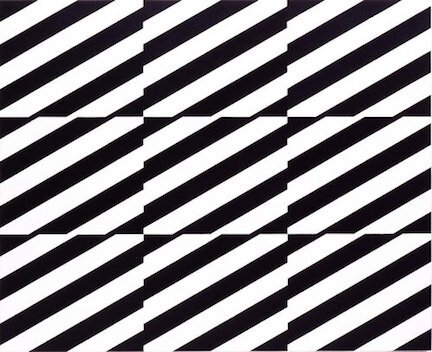

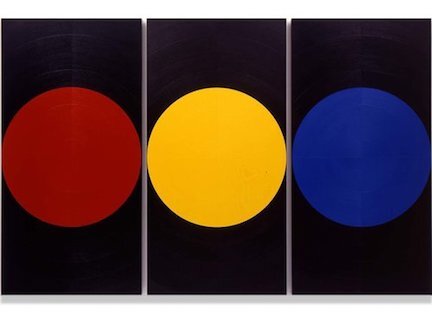

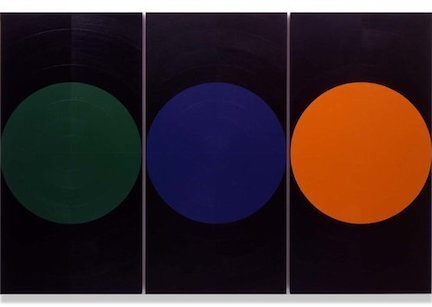

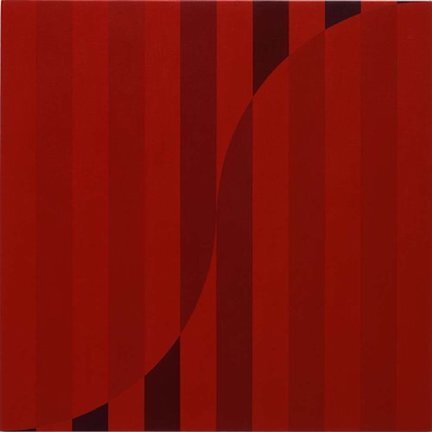

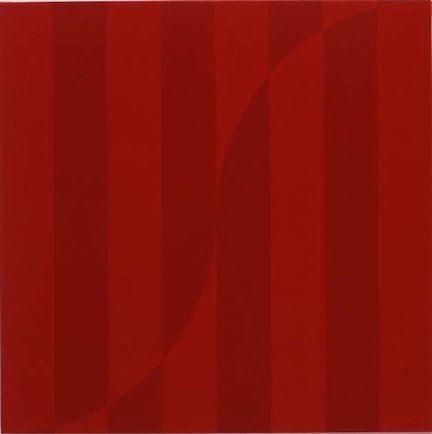

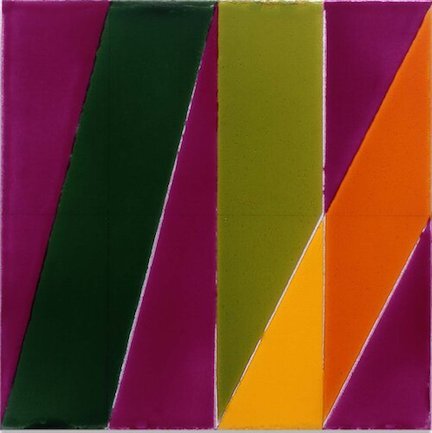

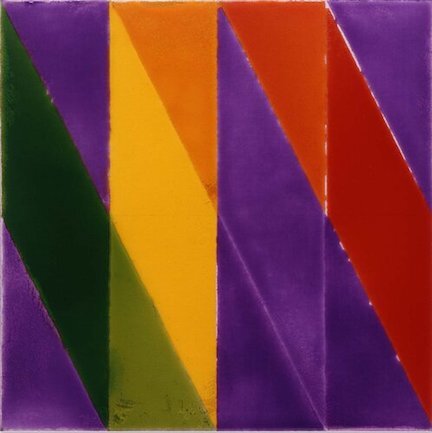

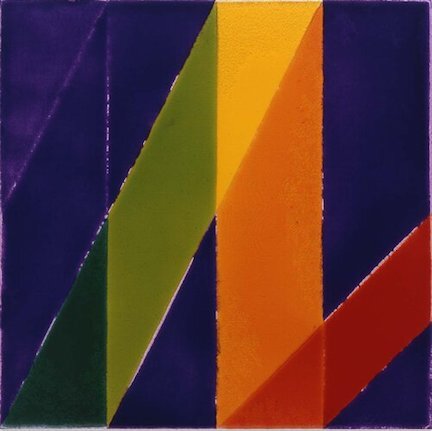

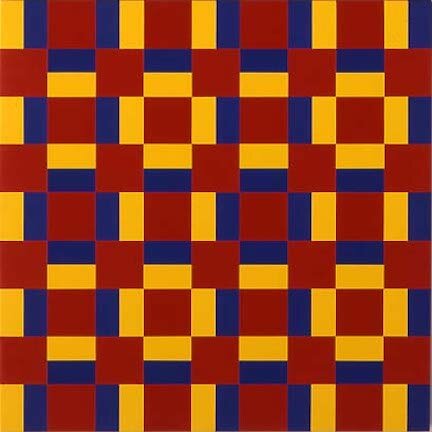

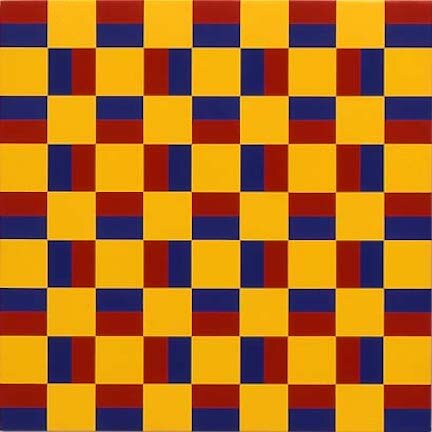

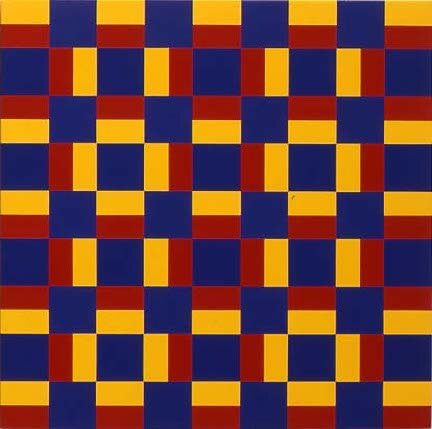

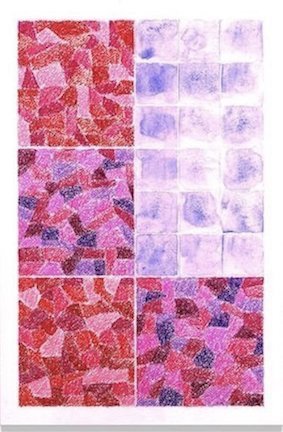

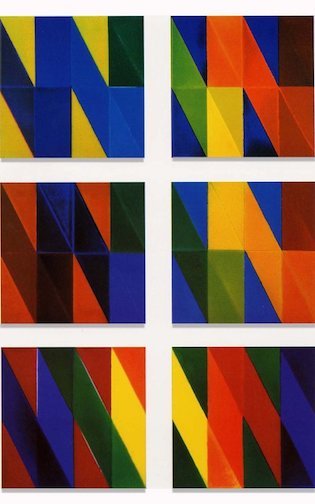

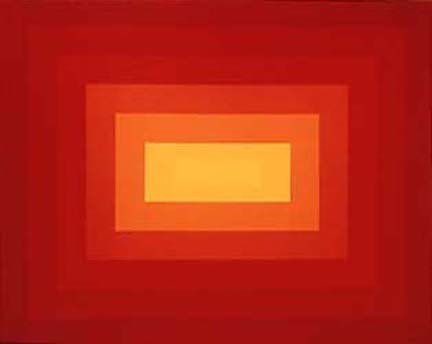

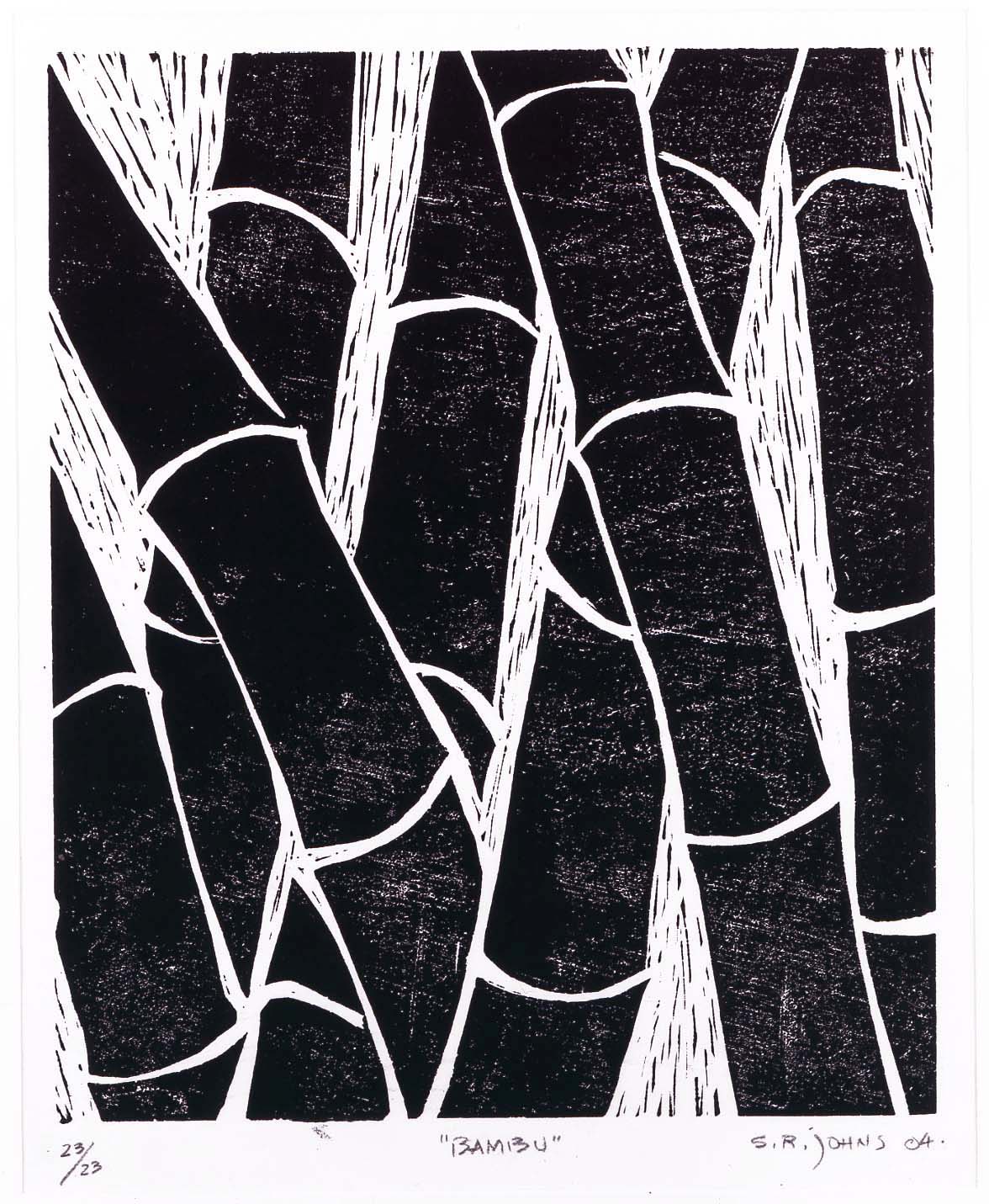

Stephen Robert Johns began his career immersed in the aura of the German Bauhaus movement, and Californian minimalism; undisputed beacons of the finish / fetish movement are John McCracken, Larry Bell and Robert Irwin, whose inspiration Johns merged with European constructivism, including Johannes Itten’s Theory of Color, in his early production. Even more direct the influence on Johns remains that of the Hard Edge movement that builds the pictorial field divided into geometric modules in which color is applied through a clear separation of the composition with marked edges, an influence he attributes to the study and process of the Hanga, or ukiyo-e, a traditional Japanese woodblock print.

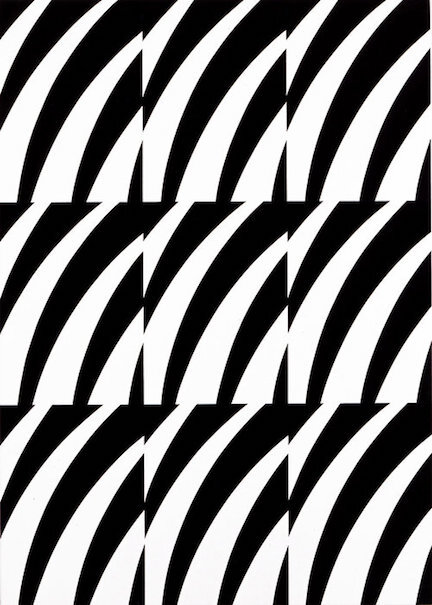

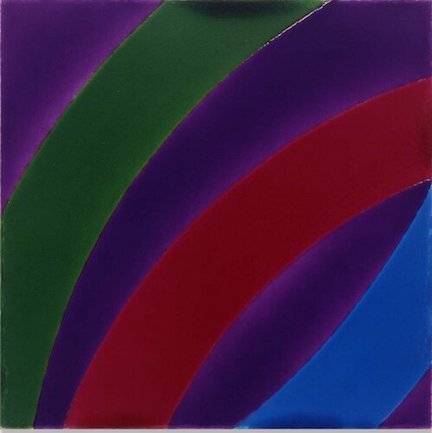

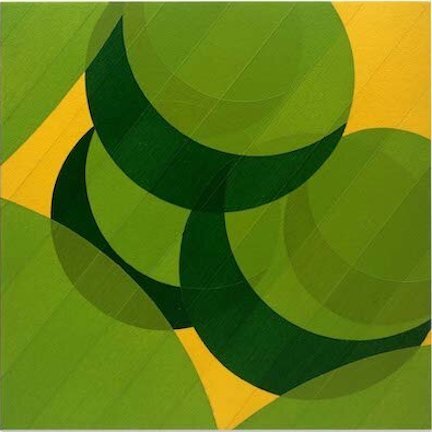

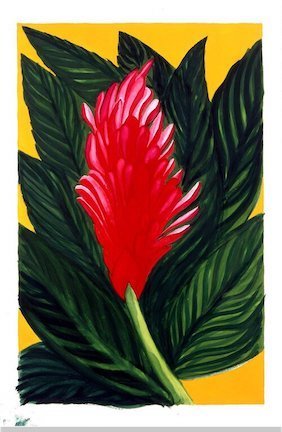

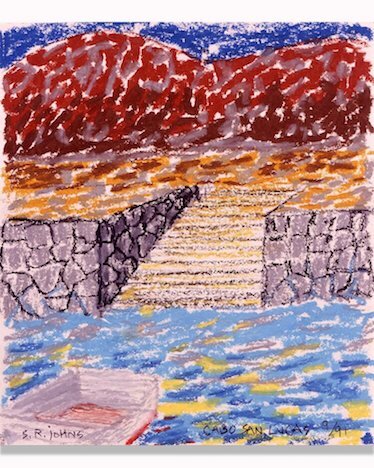

The evolution of his art over time undergoes very particular influences, such as that of the experience in the context and simplicity of a Japanese garden, and influence from the raw Mexican and Central American topography, especially in Costa Rica, in the country where he moved to live and work in 1998. The Central American experience determines the definitive evolution of his production towards a pictorial composition made of color and interlocking biomorphic forms. Nature in Costa Rica is overwhelmingly lush and opulent. it is no longer made of mountains, deserts and ocean, as in California, but of volcanic mountains, rolling hills, winding rivers and jungle where the presence of foliage and flowers is absolute, immersive and engulfing. His art moves to a radical change in which the landscape becomes prominent; real landscape and unreal landscape, a "lyrical" landscape made of color and sinuous shapes that overruns towards the pure sensuality of the environment.

The sensuality offered by nature is not seen as violent, but in retrospect it can sometimes appear aggressive in its externalization of shapes and colors because nature lives, transforms, and follows rules that have to do with an abundance of rainfall, reproduction, birth and death. The original geometric constructivism is "softened" through a marked naturalistic accent and gives way to sinuous, rounded, organic shapes. Nothing to do with the syntax of the visual perception of color and form on an early geometric basis, but a soft, serene, lyrical geometry made of contextualization of color and line within an organic composition platform.

From Ellsworth Kelly's Hard Edge and the stillness of the minimal, geometric structure of the pictorial field, Johns "escapes" towards a movement and an organicity of shapes that reminds us of a certain moment in the work of the Italian Futurist, Giacomo Balla, that captures the sensuality of a flower and transforms it into a wave of color in motion.

The sounds, the noises, the rhythms of nature are made visible by this "dance" of shapes in motion; the pictorial lines intersect and overlap rhythmically by the color as in a modern symphony, "lit", fast, at times apparently chaotic, but still orderly because nature itself is rarely chaos, but order and harmony.

The real static nature of the cultivated land, seen from the high and low altitude of the airplane in flight, acquires an unexpected movement, a new dynamism marked by the lines which, in the apparent fixity of their geometric setting, appear instead with an intrinsic movement that surprises and marvels. Johns manages to portray a somewhat imaginary movement to the documented fixedness of the cultivated land, and to represent that constant transformation of Nature in its equally constant evolution.

Cynthia Penna and her husband Renato are curators, gallery owners (ART 1307) and provide a one month residency program for artists to create and immerse themselves in their art within the historical culture of Naples Italy. The Pennas divide their time between Los Angeles CA and Naples Italy and can be contacted at: CIN@ART1307.COM

STEPHEN ROBERT JOHNS: NO MERE CONSISTENCY

By Peter Frank 2014

“A foolish consistency,” advised Ralph Waldo Emerson, “is the hobgoblin of little minds.” The dictum too often gets repeated without the “foolish,” and yet that word, that concept, is at least as significant to Emerson’s sentiment as “consistency” itself. Consistency of thought and process, Emerson was saying, need not be limiting. It need not be a prison for the creative mind, but rather a springboard. The oeuvre of Stephen Robert Johns, now spanning over four decades, proves Emerson’s point: entirely consistent in its devotion to a geometric formal language and a high-keyed palette, Johns’ painting has evolved, taken detours, and brought in factors and sources that might have seemed unlikely any earlier in Johns’ career.

Clearly, Johns derives from, and considers himself part of, the legacy of geometric abstraction that ran through artistic practice throughout the previous century. Less obviously – but logically, when you stop to re-examine his painting and consider his background and education – Johns has responded from the beginning of his mature work to the meta-optical approach favored by so many of his fellow southern California artists. The “perceptualism” of light-and-space artists such as Robert Irwin and James Turrell and of finish/fetish artists like John McCracken and DeWain Valentine proved a telling starting point for Johns – even though he did not begin with any great awareness of their work. Rather, he came to the same realizations about form, color, objecthood, and perception they did in much the same way they did – through exposure first to the possibilities of abstraction itself, then to a growing awareness of the visual conditions in which he was living his quotidian life. As Johns attests, it took his transfer from a traditional school like Chouinard, where he gained the rudiments of artistic practice, to an experimental one like Cal Arts, where he was introduced to new concepts in science, mathematics, architecture, and sculpture to give him the permission, and the formal and conceptual equipment, to develop a rationally composed but not-so-rationally perceived style.

From there, Johns was exposed to like-minded artists, already prominent on the Southern California scene, and then to the geometric modernists who had preceded them in Europe. This set the conditions for Johns’ own quasi-minimalist approach. What it left to him was a universe of decisions: what forms to paint, what colors to paint them in, what formats and materials to employ, and so forth. A neo-modernist among post-modernists, Johns enjoyed a rare freedom to evolve and even play within a clearly defined practice. It was almost as if the history of geometric art, and that of minimalism and perceptualism, has provided Johns the rules of a game within which he is encouraged to improvise.

To be sure, the pared-down language that defined (and still defines) his chosen path would not seem to allow Johns much latitude. But in fact, like any language, it is capable of a breadth of expression and displays its own poetic inflections – quite evidently, at least to those familiar with its diction. Johns, like Tony De Lap and Craig Kauffman before him – and like Auguste Herbin and Piet Mondrian before them – found a vocabulary (or, if you would, a visual identity) at a certain point and has developed it ever since.

Early on, Johns’ forms and colors served a more purely retinal investigation, serving to comprise close-hued patterns whose shifts were at once subtle and startling. His reversion to more complex, patterned images encouraged Johns to broaden his palette. He went back and forth between structures engaging many elements and those engaging just a few, until his “discovery,” at the beginning of the last decade, of the perceived world outside the frame. Johns’ exposure to Central America’s ecologies and cultures blew open his formal and coloristic range, and prompted him for the first time to approximate the conditions of landscape in his painting – without breaking stride as a geometric painter.

Geometry, and its attendant vibrant color, is the consistent factor that has dominated Stephen Robert Johns’ work from its point of emergence. But within such practice he has allowed himself great variation in form and color and even meaning. As pared down as his work can be, Johns has never allowed himself to generate easily manufactured, easily branded work; there has always been an element of experiment, even surprise, in even his most restricted paintings. Like his geometric and perceptualist predecessors, no matter how consistent Johns’ thinking has been, there has been nothing “foolish” to it.

Los Angeles CA 2014

STEPHEN ROBERT JOHNS: ENVIRONMENTAL MODERNISM

By Peter Frank 2004

Stephen Robert Johns is nothing if not a (neo-) modernist. His work concerns the relationship between the viewed and the viewer’s response to it – and, implicitly, between the artist-viewer’s response and that of the audience. Form is the common language here, allowing the artist to arrogate authority by determining the conditions of that form (and thus that language) but making him responsible for representing – or, if you would, re-presenting – his vision of the subject honestly and communicating his vision lucidly with the audience. Modernism may make a despot of the artist, but demands benevolence of that despot.

It also expects a certain faithfulness to various modernist tropes. The operative one in Johns’ art is the revision of human perception through human inventiveness. Specifically, Johns reaffirms a view of the world that has become at once broader and more detailed, at once more macrocosmic and microcosmic. He is inspired to paint landscapes not as seen from the ground, their horizon lines anchored just below the middle of the picture, but as seen from above, the horizon line absorbed into the irregular patterns of raw and cultivated topography. This is not simply the panoramic view afforded landscape painters since the Renaissance, the view from the tower or the occasional balloon; this is the view to which increasingly more humans have had access over the last century as the phenomenon of airship flight has become commonplace. This is the view that so excited Gertrude Stein as she crisscrossed her native land on her 1930s lecture tours. This is the Cubism of the gods (as the flight-besotted Futurists might have put it).

At the same time Johns reverts to the microcosmic with his equally abstracted (but still identifiable) renditions of leaves and flowers and other details of foliage. Once he lands on terra firma, he switches from geography or geology to biology, specifically (but not exclusively) botany. He trades the telescopic purview for the microscopic. But, given that his aerial views record patterns of forested or cultivated growth, Johns effectively paints the same thing from below as from above. The palm fronds and bamboo staves he renders over and over again, ringing variations on a kind of visual mantra of nature, comprise the ocean of chlorophyll that is the Central American jungle.

Wanting to capture the lush intensity of his subjects’ color, and for that matter form, Johns relies on both natural and synthetic materials. Interestingly, a case can be made that his natural material – triple-thick Washi paper – is subject to a process of synthesis in its fabrication, while the synthetic substance with which he paints – polyester resin – is a chemically derived analog to naturally occurring substances (i.e., tree resins). The issue here is not one of ecological security (these paintings are meant to endure, after all, not to bio-degrade), but of metaphorical closure with the subject matter. In functioning as notational mementos of his trips to Costa Rica, Johns’ Washi paintings remind us that, no matter how exotic, natural phenomena are inextricably bound up with our lives. Just as leaves and fields fill Johns’ visual spaces, so the dense web of the ecosphere envelops us, sustaining us in its embrace. With these paintings, Stephen Johns embraces nature back. Los Angeles CA 2004

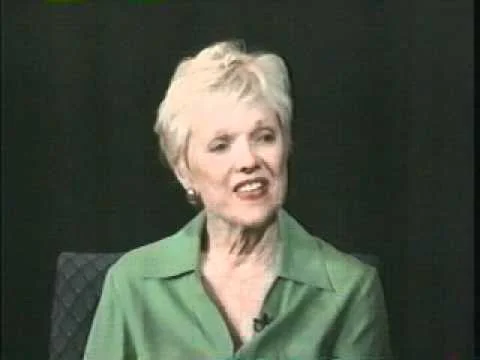

Joan Agajainian Quinn Interviews Stephen Robert Johns 2000

Excerpted from The Joan Quinn Profiles Time Warner Communications, Santa Monica CA

JAQ: Did you always want to be an artist?

SRJ: I did always want to be an artist. Probably from the early ages of childhood I was given crayons, a sketchbook, small canvases, oil paints, and brushes, which was rather unusual in comparison to the kids I grew up with...

JAQ: Why did you choose Chouinard Art Institute, when there were so many other art schools around?

SRJ: I chose Chouinard because of my grammar, junior, and high school teachers. All recommended Chouinard, so when it came time to graduate from high school and I was asked, “what do you want to do with your life? Do you want to go into the service? Do you want to enter college”, I responded that I wanted to go to Chouinard, and study art. I had no idea what the school looked like or where it was located. I just knew that it was in Los Angeles and came highly recommended.

JAQ: That’s how you decided?

SRJ: That’s right. I was a young surfer, you know, growing up in the Pacific Palisades/Santa Monica area. I wasn’t familiar with the Los Angeles area. And, of course, Chouinard was downtown, near Westlake Park. It was quite a culture change for me to see the inner city. I’d led a very sheltered life.

JAQ: Do you hang out with other artists? Is that an important part of your life?

SRJ: Oh, absolutely. If you can’t interact with other artists, I think you’re missing out on something important. I really didn’t do much of that over the past (20) years. But recently I received two fellowships to travel to Costa Rica and paint at the Julia and David White Artists’ Colony. There I met artists from the US & Europe, as well as outside of the artists’ colony, in San Jose galleries and museums, where I was introduced to Costa Rican artists.

JAQ: How long ago was that?

SRJ: Well, my first fellowship was in 1998, and my second fellowship was in 1999.

JAQ: When you were at the artists’ colony, did you work with other artists from different countries, or just artists from Costa Rica?

SRJ: Artists come to the Julia and David White Artists’ Colony from all over the world. I did learn a lot about the Costa Rican culture because I met artists down there who were Costa Rican. At the art colony I was mostly isolated, however, and the only other guests were artists in residency, such as in 1998- a watercolorist, Patricia Tobacco Forrester from Washington, D.C, and Phil Higgs, a writer from New York. We would interact during lunches and dinners. The art colony is located in Ciudad Colon, a very small farming community, about (45) minutes west of the capital, San Jose. The studio space and the spacious landscaped grounds are very good for committing yourself to your work, with few distractions.

JAQ: Then there are other types of artists who reside at the Costa Rica art colony besides painters and visual artists?

SRJ: Yes. Fellowship recipients include music composers, musicians and writers.

JAQ: What a great program!

SRJ: It really is. We could talk with each other every day, usually during meal time, and discuss the experiences we were having, while doing our art at the art colony, as well as interacting with the community outside of the art colony, whether in Ciudad Colon or in San Jose.

JAQ: It’s like the American Academy in Rome where the have many different types of artists come to live and work together.

SRJ: Exactly. We shared meals, as well as problems and successes with our work and our life. I was introduced to galleries in Pavas and San Jose, where I met other artists. Some of these artists are quite prolific in Costa Rica as well as internationally. It really made me feel more complete as an artist and as a human being, making friends with these artists from Costa Rica, attempting to speak Spanish and them trying to speak English, forged in conversation by our love for art, almost like taking me back when I was in art school- a newness!

JAQ: In art school, did you have art idols, artists whose work you loved, who you thought about constantly?

SRJ: Oh, yeah. Michelangelo has always been just the most astounding artist in my eyes, and of course, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse & the Bau Haus artists. There is a great time difference between those great artists. Yet, the way they were able to draw anatomy, a person or capture a human feeling within their compositions, and their use of color made them equally inspiring to me. I also have to include Ellsworth Kelly. I love his reductive paintings!

JAQ: Has working as a garden landscape designer influenced your painting, or has your painting influenced the landscape work?

SRJ: Both. They really do mesh and interact. And at night, I’ll sometimes go to bed thinking about a stone wall that I’m building for a landscape project or possibly a specimen tree that I want to plant in a particular landscape composition. At the same time, in the studio, I have my painting series, which has been evolving over the years. It’s a nice balance of creativity. They are both serious works in progress for me.

JAQ: So, does this painting Guatemala City, remind you of a landscape?

SRJ: Yes. This painting reminds me of a particular view I observed from the air, while coming into Guatemala City very early in the morning, just before dawn. It was still dark, but illumination was visible from lightening strikes on the ground, back lighting the trees below. It really is sort of a top-view painting, similar to an architectural landscape rendering, looking down on a city surrounded by the jungle, inundated by rainwater and reflective light.

JAQ: You do see the trees, but they are abstracted.

SRJ: Geometry still plays a key roll within my compositions. I think before my trips to Costa Rica, I didn’t see trees, leaves or plants as subject matter in my work. My compositions then were primarily pure geometry and color. There is now a new element influencing my art- nature.

JAQ: Those fellowship residencies you received from your LA gallery really did make a big difference in your vision, even though you were already working outside, as a landscape designer, with nature.

SRJ: I was landscaping and I was painting. The landscaping and the painting were two distinct professions for me to be creative with, and in some ways inspired from. I may be working on both of them during the same day, week or month, but I really couldn’t bring them together- in other words, paint the landscape I created. They were two separate entities. Now, after my stays in Costa Rica, it seems that I go to bed at night thinking about landscape projects and painting. And, I have the art colony residencies to thank. I became inspired to create the landscapes on the ground and from the air!

Joan Agajanian Quinn, the former West Coast Editor of Interview Magazine, spent nearly twenty years as a member of the California Arts Council. She currently serves on the California Film Commission and the Beverly Hills Architectural Commission. Joan Agajanian Quinn writes for Art Talk, Art Review, and Inside Events. Her cable television show The Joan Quinn Profiles, can be seen on a mini-syndicate across the United State. Time Warner Communications July 2000

STEPHEN ROBERT JOHNS IN COSTA RICA

By Peter Frank 2001

Even for an artist as dedicated, formally and conceptually, to logic and symmetry as Stephen Robert Johns, the experience of what might be called the extra-logical can have profound impact. Such experience, as Johns demonstrates, need not compromise an orderly foundation to register its effect.

Indeed, it can be on that very intersection between what seem mutually exclusive or contradictory factors that an enriched art emerges.

Until he began his visits to Costa Rica, Stephen Robert Johns explored color through refined, even restrained compositional formulas, formulas so readily comprehendible that they in effect effaced themselves, the better to allow color its inherent glory. This, demonstrably, paid nature honor: Johns was not seeking to improve upon nature through refinement or edition, but to concentrate on nature’s impact, retinally and thereby psychologically, upon us humans. The question of how (and what) we perceive – a prime concern among many of the abstract artists working in Los Angeles – engaged Johns, as did the desire to “know” elements of nature, notably color, absent the contexts and referents that bound our experiential understanding of such phenomena.

At the same time, Johns knew that color couldn’t completely be isolated from its context(s) in the world. His “pure” paintings, like those of Malevich, Mondrian, and other theoretical heroes of 20th century art, are pure only for the brief moment during which we regard them as pure – as idiom momentarily transcending inflection. Before, after, and in some part of our minds during, this moment, we see colors if not as symbols, then as suggestions of real, palpable things – yellow the sun, red fire, green vegetation, blue sky, to name only four especially elemental inferences. The pioneers of abstract art had hoped at least to signal abstract sensations, but even there they found it impossible to trigger for long the apperception of love, anger, envy, hunger, sleep, or lust. A color might have psycho-physiological properties – it might induce sleep, or even suggest its qualities – but, if anything, these interfere with its metaphysical properties. A color might induce or suggest the state of sleep, but, precisely because of these active effects, it could neverembody sleep. A color is abstract, ironically enough, only in relation to another color.

Johns’ first trip to Costa Rica allowed him to move beyond this dilemma by giving him permission to engage color referentially, to complicate composition so that the references he was now accepting (or, more accurately, bringing) into the painting took on a greater concretion. Of course, Johns was not moving towards literal description, but towards evocation. His new-found stylizations, disrupting the symmetries and lockstep rhythms of earlier series, brought his art to a new pitch, less ideal, less luminous, more sensuous, more recognizable – and yet not readily identifiable, not entirely voluptuous, not lacking in inner light or conceptual refinement. In his works from – and since – his first trip to Costa Rica, Johns has met the world half way.

This relinquishing of rigid formula was an aesthetic voyage waiting to happen, one triggered by a geographical and spiritual voyage. Johns’ introduction to a very different place gave him permission to “know” in a different way what, and where, was familiar to him. Johns’ introduction to Central America certainly provided him a gateway to a whole new universe of experience; like Paul Klee – who introduced color into his work as a result of his visit to North Africa in 1911 – Johns let his visit to another universe a few miles south have a radical but entirely comprehendible effect on his approach to his art.

In certain aspects, the overwhelming experience of Costa Rica reified conditions already manifested in Johns painting: color is of prime importance, form is smooth and regular, texture is (surprisingly) soft and sensuous, and composition is deceptively regular and repetitive. These conditions determine a groundwork for artistic evolution that can prove quite supple; what is surprising is the nature of Johns’ evolution, away from the self-effacing fixity of the earlier Sector-series paintings and towards a

much more asymmetrical approach – and yet there is little if any change in the color, the grammar of shapes (the vocabulary modified enough to allow in the new landscape), or the firm draughtsman’s line with which everything is described.

Johns’ visual thinking has in fact always been sourced in landscape. What has changed is how apparent that is to an uninformed (if still reasonably sophisticated) eye. And what has surfaced is the surface of the earth, the patterns and colors of a topography seen from above. Johns has spoken of the impact that seeing the

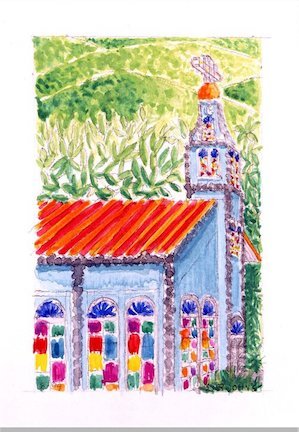

farmland of central California from the air had on him as a boy. Similarly, the Costa Rica painting cycle began in his mind as he flew into Central America the first time. On its way to San Jose, his plane made a stop in Guatemala City, bringing Johns up close for the first time to the tropical rainforest – and to the rooftops of a Spanish colonial city. The intensity of the colors and elaborateness of the shapes he saw in both natural and manmade realms set in motion a re-evaluation of composition and palette that his stay in the region only heightened.

Since that experience and that visit, Johns has retained the sensuousness of the real world in his painting – not just the sensuousness of color, which has always been his domain, but a formal sensuousness equal to, and enhancing, the color’s. This has not meant a diminution of formal rigor; on the contrary, the new compositions require more consideration, so that their evocation of the external world can be modified without being suppressed. Stephen Johns’ task is, after all, not to replicate the seen world, but to distill it into unencumbered retinal experience. What he has found is that such experience begins encumbered, by unavoidable association, and that the oblique associations he can bring to each picture serves to pre-empt the associations we might bring. If anything, Johns’ color is freer than ever.

Peter Frank Los Angeles CA 2001

STEPHEN ROBERT JOHNS - AERIAL VIEWS, JUNGLE RHYTHMS

By Peter Frank 1999

Even more than most artists working in a geometric manner, Stephen Robert Johns derives his art as much from extra-formal sources as from formal reasoning. There is in Johns' work a "real-world" resonance, something that imbues the retinal dynamics of point and line on a plane (as Kandinsky put it) with a more "viewer-friendly" dimension. Not that the dimension of Euclidean (and non-and post-Euclidean) formulation is incapable of attracting and rewarding viewers' attention. But, as Johns' work increasingly evinces its symbolic and sensuous as well as retinal factors, factors which point to phenomena beyond the literality of the canvas, he now allows (without actually encouraging) viewers the opportunity to "read" as well as see his compositions,

and to recognize ranges of experience that might resemble their own.

This does not mean we can regard Johns' paintings as abstracted people, places, or things. Such abstraction can feed, however obliquely, into his work, but is no more now than ever its raison d'etre. Rather, it means that Johns has moved into a practice of marking and coloring once exercised by such painters as Mondrian, Torres-Garcia, and Kandinsky himself, a practice in which the derivation of geometric form from natural and quotidian sources (or at least their conceptualized essences) was a common practice. As neutral and obdurate as Johns' work can often seem, it is always motivated by something recognized (if not truly recognizable) outside the sphere of design or compositional reasoning even as it invariably returns to that sphere.

Johns' initial, and basic, extra-formal source was his childhood memory of farming patterns seen from the air as he flew over California's central valleys. The abstracting view of the land - especially the land as modified by human intervention - has beenan inspiration for artists of all kinds ever since they started ascending.

From early photographers' land and cityscapes made from hot-air balloons to the Cubists' and Futurists' dynamic romanticization of air flight and the enchantment Gertrude Stein felt travelling by air over America (which helped mute the disdain she'd maintained for her native land), the artists of the modern era(s) have reveled in flight and the unprecedented visual stimuli it has provided them. Neo-Modernist Johns thus follows in a latter-day tradition.

He has as much as declared his faith in this tradition with his Sector Series, an extended sequence of paintings that have been neutrally formatted (12-inch-square) and neutrally composed (regularly and repeatedly sectioned according to various gridded or otherwise patterned structures), and painted with resin, giving the colors an intense saturation even as it neutralizes the paintings' surfaces. Since his extended visits to Costa Rica, however, Johns has made yet more apparent his response to what is in effect the partial abstraction of nature into cartographic ciphers - ciphers relieved of the kind of symbolic function they perform in actual maps.

The Costa Rica travels inspired Johns into even more fervid aerial abstraction, affording him (among other provocations) the bulbous form of tree foliage and the vivid lushness of the Central American jungle’s green – In contrast to the more balanced, multi-spectral patterns he derives in his Sector works from the crops, water sources and gridded roads of California. His experiences on the ground, however, have also proved fruitful (the pun intended). Jazzed by the vegetation, by the vernacular architecture of peasant churches, by the custom of painting everything in bright colors – right down to the fences, which serve as a kind of non-objective mural site – and by other rich sources of (literally) local color, Johns has returned from his two southern sojourns with several new bodies of work. Some works on paper go so far as to depict foliage and figures as well as landscape in a flat, stylized, but still readily recognizable fashion. Other works (on paper and canvas) display rolling, rippling bands of green and yellow cascading on one and another

in almost banner-like evocations of verdant hills. Still others find a handsome, slightly eccentric constructivism in multi-colored compositions responsive to the architecture of the region.

These works prompt us to think back to any number of modernist models: the colored disks, for example, of Robert Delaunay (which were themselves so heavily based in architectural forms, from Romanesque churches to the Eiffel Tower); the rhythmic machine-scapes of Fernand Leger; and the system Theo van Doesburg devised for abstracting natural forms according to a several step progression of increasing simplification and classicization. Johns has made this rich but recently neglected heritage his own, re-exploring and re-valorizing the process of abstracting from nature and divesting it thereby of its decorative, artificial associations. No, actually, Johns re- valorizes those associations as well, regarding decorativeness and even artificiality as central to artistic conception and formulation – at least as central as is the spontaneity and naturalness to which we have expected painters (at least since the Abstract Expressionists) to aspire. Johns is among those painters capable of finding the spontaneous and the natural in decoration and artifice – and finding the decorative and the artificial or at least artful, in the spontaneously natural and the natural spontaneous. If it’s a jungle out there, Stephen Robert Johns demonstrates, our eyes are the richer for it.

Los Angeles CA 1999

Peter Frank is Art Critic for the L.A.Weekly. He has served as critic for the SoHo Weekly News and theVillage Voice in New York, and as Editor of Visions art quarterly in Los Angeles, and has edited and written for many other publications around the world. He has also organized numerous exhibitions for museums and galleries, including the Guggenheim Museum, P.S. 1. the Alternative Museum, the Center for Inter-American Relations, and Artists Space, all in New York, Otis Art Institute and the Contemporary Arts Forum in California, and other organizations – including the New York-based Independent Curators Inc. and Germany’s Documenta. Frank has taught and lectured throughout North America and Europe, and has published several books, including New, Used & Improved: Art for the `80s; Something Else Press: an Annotated Bibliography; and a book of poems, The Travelogues.

Molly Barnes Interviews Stephen Robert Johns 1999

Stephen Robert Johns is a wonderful painter who covers a lot of territory in his work. In his life as well as in his paintings, he applies a strict discipline of excellence and a caring for his craft that is a joy to see in an artist today. Stephen's paintings are pristine, yet, unlike his idol Ellsworth Kelly, he has gone from painting minimalist geometric art, which he began while a student at Chouinard Art Institute, to painting reductive landscapes and natural settings.

Johns particularly enjoys painting the verdant landscapes of Costa Rica where he recently spent time. Stephen Robert Johns grew up in Los Angeles in a typical Southern California family, with an aerospace father and a homemaker mother. He has supported him-self for years as a landscape designer to the stars and CEOs of Los Angeles.

His recent solo exhibition at LA ARTCORE is comprised of both paintings and works on paper. The works are reflective of his days at Chouinard & Cal Arts, these paintings embodying bright, hard-edged shapes in a style reminiscent of Al Held to the more lyrical abstractions that remind one of Richard Diebenkorn's "Ocean Park" series.

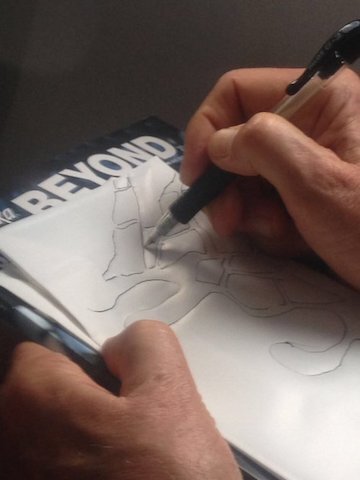

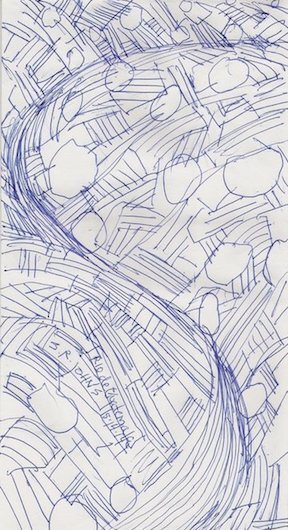

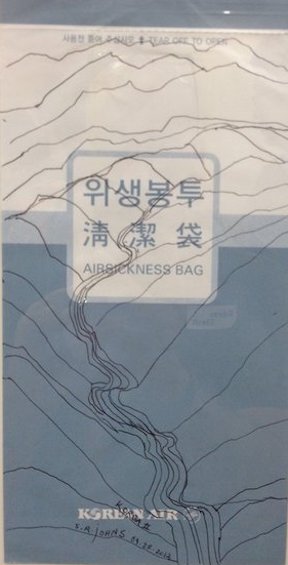

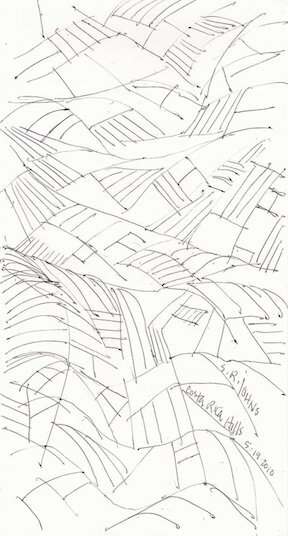

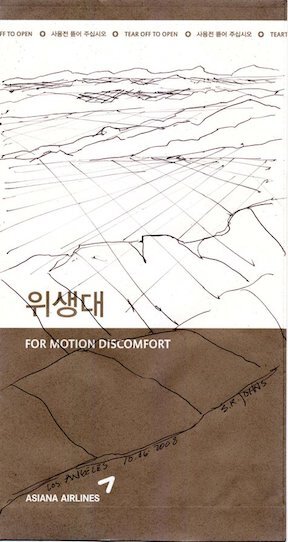

My favorite paintings are of Johns' aerial views inspired by actual images seen from the air above Costa Rica moments before landing. These images are rich in bright blues and greens combined and blended with abstract elements representing trees and rivers and various solid geometric shapes. The images depicted are reminiscent of final scenes in the Jerome Hellman film "The Mosquito Coast." Johns however does not work from photographs. Instead, he paints from sketches he has drawn on "air sickness" bags while on the plane. These bags are also included in the exhibit. Johns' love of life, art and the beauty inherent in nature are communicated in this recent interview.

MB: When did you realize you wanted to be a fine artist?

SRJ: As a student in grammar school, my teachers and my family pushed me to do more art. They encouraged me because my of ability to draw was a little better than that of the other students.

MB: Were you always the best in the class?

SRJ: Usually. In high school my art teacher referred me to Chouinard Art Institute, which has since transitioned into the California Institute of the Arts. My teacher suggested I send a portfolio of my work to the school. At the time I had no portfolio to send, other than a few class assignments, so when I returned home, I rendered a few album covers that belonged to my parents, and embellished them with paint and sent them along with class assignments off to Chouinard. I was accepted right away with a limited scholarship.

MB: How is your nine to five job different from your painting?

SRJ: My landscape design is very similar to my painting. I usually can’t stop thinking about an idea I may have for a painting or a landscape design. I’ll be consumed by the thought of the presentation all day and all night before 1 do it. Just as I prepared for painting by just living life, the same can be said about my landscaping. I like to submit a plan of what I will do for my clients, though often I come up with an idea that is totally my own, and sometimes completely different from what the client thought they would like.

MB: Who were your early influences?

SRJ: As an art student, I was an illustrator. I enjoyed drawing comic characters, life drawings, nudes; From this I derived a lot of enjoyment. I had weak skills in color and geometry. In my graduate year in art school, I began doing minimalist color field study paintings. Color theory studies of Bauhaus artists such as Johannes Itten interested me particularly. The artists I admired most were Ellsworth Kelly, Picasso, Henri Matisse, Oskar Schlemmer, Lionel Fenninger and Frank Stella.

MB: Who is your favorite artist today?

SRJ: Ellsworth Kelly. I like the way he works from nature, reducing form to a minimalist state.

He does the same thing with color. I find that to be a pure statement.

MB: If you could own one piece of art by an artist living or dead, who would it be?

SRJ: Of course it would be Kelly. Possibly Picasso. He delved into what an artist is thinking. People often feel he ripped off ideas from other artists; I feel he studied what other artists were doing, became inspired and applied that inspiration to his own vision as an artist. He was so unique. He didn't limit himself to only painting or sculpture. He also created stage designs and worked in clay. Similarly, he traveled all over the world, never limiting himself to one place to create his art. His inspiration came to him so effortlessly.

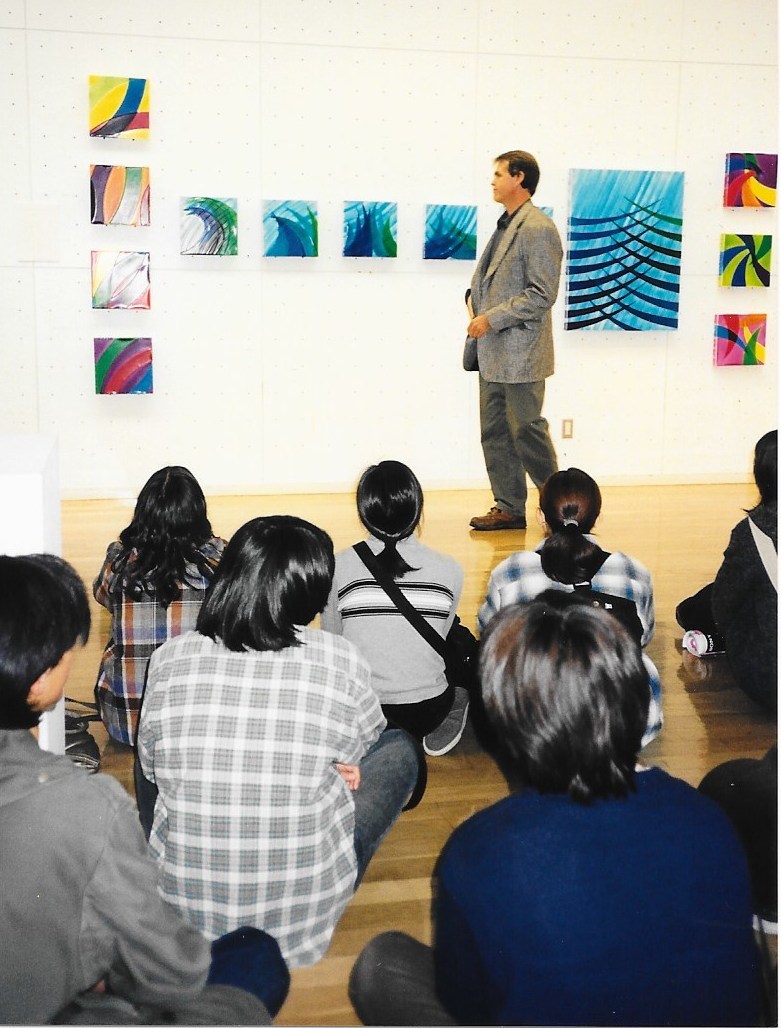

MB: Do you think dialogue with other artists is necessary for artistic growth?

SRJ: Absolutely. Being part of LA ARTCORE has been an exceptional experience. When I taught art at the Junior Arts Center at Barnsdall Park, I interacted with other artists, but on a more academic basis. When I met Lydia Takeshita, the Director of LA ARTCORE, I learned to communicate my feelings about art in a dialogue with other working artists. The development seemed to be a natural process, and my work began to change as a result. This was new for me.

MB: You were recently offered a fellowship to live and work in Costa Rica and you have said that the trip changed your life. How so?

SRJ: There is an amazing art colony there. It’s run by William White, and is called The Julia and David White Artists’ Colony. Being there changed my thinking entirely. I was introduced to many wonderful artists at the art colony- artists from all over the world, and artists representing a totally different culture that I was unaware of- Costa Rica. These artists I met in Costa Rica were “world savvy”. The energy I found within that artistic community was phenomenal. As an artist, I was accepted into their group as one of them. When I arrived, I was pretty burned-out with my hardedge paintings. I felt I needed a change of style with my painting. I certainly didn’t travel to Costa Rica to do this. My gallery director, Lydia, offered me a fellowship to paint in Costa Rica for a few months and I accepted. My art required a jolt, and I got it, experiencing the beauty of the Costa Rican landscape- especially from the air when our plane flew in; and the culture, as well as the interaction with the local artists...it was all very profound.

MB: Do you believe in God?

SRJ: Yes. I have always believed in God and that the point of religion was to enforce people’s perceptions of reality, purpose in a positive manner, and enhance their society as well as maintain some kind of moral and social order.

MB: Did spending time with artists from Costa Rica change your own belief systems?

SRJ: Yes. The artists I met in Costa Rica affected my beliefs considerably, especially Roberto Lizano, Luis Chacon, Mario Maffioli and Fabio Herrera. They are members of an independent art movement Bocaraca. They are confronted daily with there own feelings about life in a Central American country, as well as when traveling abroad. They paint and sculpt scenes related to everyday living, yet with such bravado and enthusiasm. Really fresh stuff!

MB: What is the Bocaraca and how do they operate?

SRJ: The Bocaraca are a select group of 10-12 artists who live and create work in San Jose, Costa Rica. They have been interacting over the past 15 years and are of different ages and sex. They dialogue and support and critique each other’s exhibits. They are exhibiting their work on a regular basis, in local galleries as well as in a number of museums. These artists are no strangers to world travel, with most of them showing in galleries and museums in New York, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Germany, Spain, France and Italy.

MB: Here in LA we hear about the Day of the Dead. How is it celebrated in Costa Rica?

SRJ: It’s a Latin American celebration paying respect to family members and close friends who have died. It’s such a big deal in Costa Rica- the costumes and the activities, especially for students. It really reminds me of being back in Los Angeles.

MB: At fifty, looking forward, what do you plan for the next half of your life?

SRJ: I plan to continue to do my art and to continue to design gardens. However, I would prefer in the future to focus more closely on my painting. It has been a large investment of my life, and I feel I have a lot to give- much more so now than I did ten years ago.

MB: What is your favorite color?

SRJ: If you had to pin me down to a favorite color, I would have to say blue. To me, blue is one of the strongest spectral colors. Inclusive to the color blue is turquoise, as well as the depth of blue-violet. Actually, now that I think about it, my favorite color is lime-green!

In summation, Stephen Robert Johns is an abstractionist who has returned to nature for his inspiration. With such dedication coupled with the obsessive need to paint, how could Johns do anything else, and why would he want to do anything else but continue making beautiful paintings? Johns is one of the lucky ones, being an artist, because after all, inspiration is what the artist’s life is all about.

MOLLY BARNES, 1999

* Molly Barnes has been an art dealer and gallery owner in Los Angeles and New York for the past thirty years. She is also a writer and radio personality and recently received an award from LA ARTCORE for her outstanding contribution to the arts in Los Angeles CA